When designing an intervention for forest ecosystem restoration in developing countries – such as the reforestation of a landscape, the adoption or expanded use of agroforestry practices, or the facilitation of a forest carbon project – the Free, Prior, and Informed Consent (FPIC) of the local communities is paramount, particularly with regards to the real and potential risks associated. As opposed to the top-down financial risks taken on by an environmental, social, and corporate governance (ESG) investment endeavoring to offset corporate GHG emissions or a philanthropy’s reputational risks in supporting sustainable development, the on-the-ground stakeholders are significantly more exposed to the potential of adverse or unforeseeable effects from an imperfectly planned forest restoration project. These risks must first be assessed, planned for, and mitigated to ensure that rural smallholder and indigenous communities can be properly empowered as the stewards of a restored ecosystem without exposing them to additional challenges in doing so.

Within the context of international forest ecosystem restoration, particularly in the rural communities of developing countries, the expertise and capacity to assess risk and make informed decisions accordingly is often limited, inconsistent or lacking. Similarly, public, private and civil society stakeholders, and most significantly, on-the-ground smallholders and communities often lack the capacity and resources to quantifiably assess and respond to the risks of engagement within the forestry sector. These risks are varied and often opaque, ranging from the opportunity cost of a new process that could limit the cultural uptake of an intervention to changes to the water table.

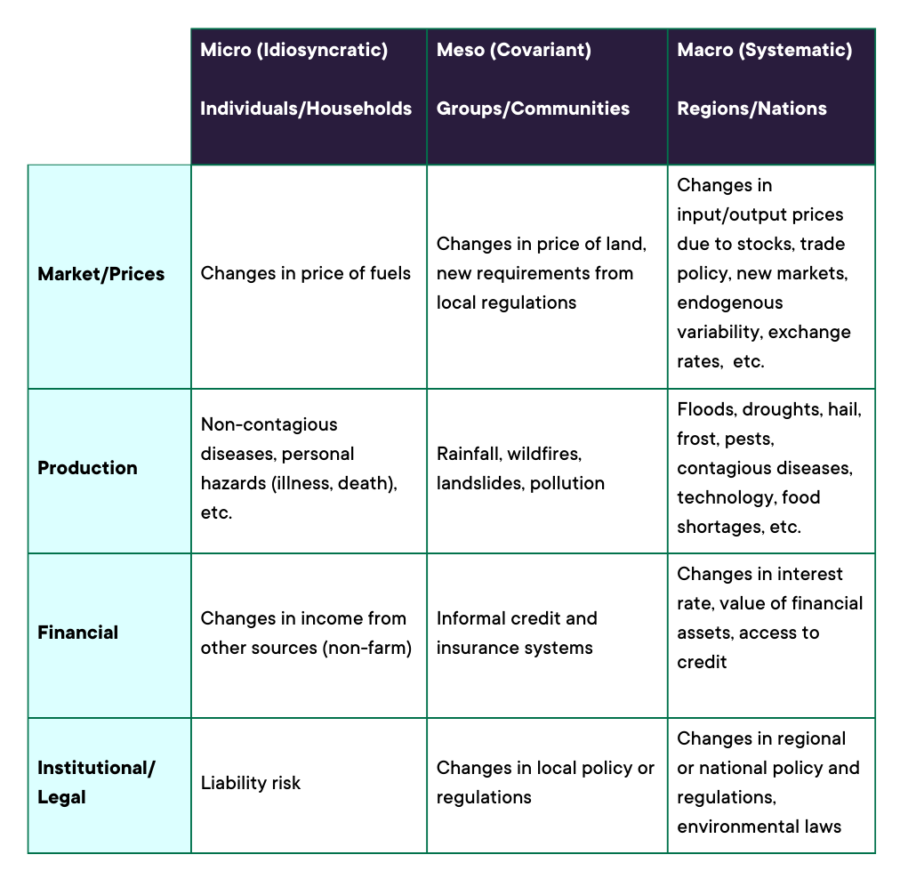

The chart below highlights some of the potential risks that must be assessed and mitigated to ensure the permanence of any forest ecosystem restoration or agroforestry intervention.

First and foremost, practitioners must develop strategies to mitigate identified risks. This may include diversifying income sources, implementing climate-resilient practices, and seeking insurance options. Approaches must then be established to ensure that smallholders have access to the necessary resources such as seeds, tools, and credit. Lack of resources can be a significant risk factor. Whether to support the development of ecosystem restoration, agroforestry for subsistence or market, the development of forest carbon credits, or a combination thereof, some of the best practices for risk assessment and decision analysis include:

Socio-Cultural Best Practices:

- Local and Community Context Assessment: Develop an understanding of the local socio-economic, environmental, and political context. Smallholders often face unique challenges, tailoring risk assessment to the specific region and community.

- Stakeholder Engagement: Involve smallholder landowners in the decision-making process from the beginning, cultivating local and traditional knowledge and priorities can be invaluable for risk assessment and promote buy-in.

- Collaborative Networks: Promote collaboration and networking among smallholder landowners, local organizations, and government agencies to share knowledge and resources.

- Social and Environmental Impact Assessment: Assess the potential social and environmental impacts of the project, and ensure that they align with the priorities and values of the local community.

Implementation Best Practice:

- Diverse Tree Species Selection: Promoting the planting of a variety of tree species with different growth rates and uses. This diversification can mitigate risks associated with climate, disease, pests, and market fluctuations.

- Site Suitability Analysis: Conduct thorough site assessments to determine the suitability of the land for agroforestry or reforestation, considering factors like soil quality, climate, water availability, competing interests, trade-offs, etc.

- Risk Identification: Identify potential risks specific to the project, such as weather-related risks (droughts, floods), market price volatility, land tenure issues, regulatory changes, political instability, etc.

- Training and Capacity Building: Provide training and capacity-building programs for smallholders to enhance their skills in tree planting, management, and sustainable farming practices.

Financial and Legal Best Practices:

- Financial Risk Assessment: Evaluate the financial risks, including the initial investment, ongoing maintenance costs, and potential revenue streams. Develop financial models that account for different scenarios.

- Market Analysis and Market Linkages: Conduct market research to understand the demand and supply dynamics for commodities, in order to facilitate linkages with markets and value chains to reduce market-related risks.

- Legal and Land Tenure Considerations: Address land tenure issues and ensure that smallholders have secure land rights. Legal uncertainties can pose significant risks.

Management Best Practices:

- Adaptive Management: Implement an adaptive management approach that allows for flexibility in project implementation. Smallholders should be prepared to adjust their strategies based on changing conditions.

- Monitoring and Early Warning Systems: Establish monitoring systems to track the progress of agroforestry or reforestation projects. Implement early warning systems for climate-related risks.

- Long-Term Planning: Encourage long-term planning and sustainable land management practices. This can help mitigate risks associated with soil degradation and resource depletion.

To learn more about how to plan for and mitigate on-the-ground risks, consider joining our International Forests Working Group (working group participation is open to 1t.org US pledges). Email Trey Lord to learn more.

Sources:

Journal of Rural Studies, Agroforestry transitions: The good, the bad and the ugly